by Ron McCoy

Those of you who regularly check out this column know it frequently addresses goings on associated with the United States’ Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990. Although NAGPRA recently figured in a thus far unsuccessful attempt to “repatriate” an orca from Miami’s Seaquarium,[1] the aspect of this law that usually garners attention here is somewhat different. That’s because ATADA’s intended audience composed of of curators, dealers, and collectors of tribal art are probably more concerned with the law’s provision for repatriating certain types of objects of indigenous (American Indian and Native Hawaiian) origin from institutions which satisfy its broad definition of “museums.”[2]

NAGPRA zeroes in on “cultural items”[3] falling into one or more of five categories: human remains, associated funerary objects, unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, and cultural patrimony. Of these categories, two receive attention here: sacred objects and cultural patrimony. (Occasionally, because of historic or other considerations, we also take note of transfers involving unassociated funerary objects.)

Under NAGPRA, a “sacred object” is a piece “needed by traditional Native American religious leaders for the practice of traditional Native American religions by their present day [sic] adherents.”[4] As for “cultural patrimony,” a piece qualifies for inclusion in this category if it has

“ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the Native American group or cultural itself, rather than property owned by an individual Native American, and which, therefore, cannot be alienated, appropriated, or conveyed by any individual regardless of whether or not the individual is a member of the Indian tribe or such Native American group at the time the object was separated from such group.”[5]

Occasionally, notices of intent to repatriate per NAGPRA appear in the Federal Register. These represent the agreement reached between one or more claimants and the museum (as defined by NAGPRA) responsible for the item(s) in question. That agreement specifies the party or parties to which the item(s) will be repatriated by the museum, pending the filing of a competing claim. Unless otherwise noted, quotations include here are drawn from those notices.

Haudenosaunee/Iroquois Miniature False Face Mask

Sacred Object/Object of Cultural Patrimony

Colgate University, Longyear Museum of Anthropology, Hamilton, NY (Oct.9, 2019): Sometime early in the twentieth century an unidentified member of the Oneida Indian Nation gave Hope Emily Allen (1883-1960),[6] an independent scholar of some renown who focused on medieval mystical traditions, “a miniature false face mask or medicine mask,” which she “added to her own personal collection.” The little mask remained with Allen throughout her life. In 1962, two years after her death, it was sold to the museum.

This notice does not describe the piece, but relies, instead, on the sort of standard language one associates with Haudenosaunee repatriation claims dealing with False Face masks; specifically, these “are not only sacred objects used in the performance of medicinal ceremonies, but are also considered objects of cultural patrimony that have ongoing historical, traditional, and cultural significance to the group.”

The museum determined that for purposes of NAGPRA the miniature mask was both a sacred object and object of cultural patrimony which should be repatriated to the Oneida Indian Nation in New York.

Three Tesuque Ceramic Vessels, Comanche Dance Headdress and

Painted Buffalo Robe

Sacred Objects/Objects of Cultural Patrimony

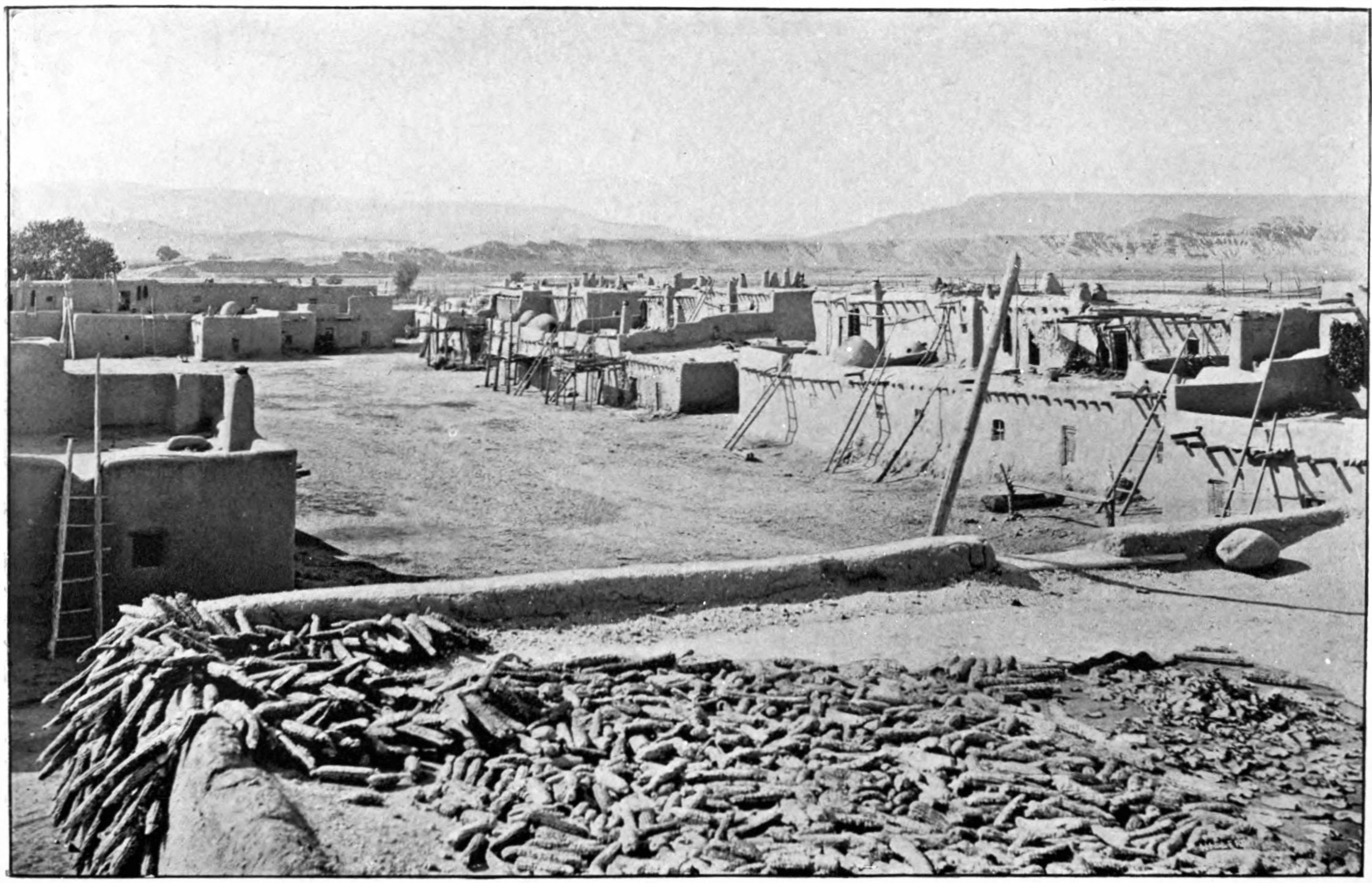

Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY (Oct. 9, 2019): This notice deals with five items: three ceramic pieces – a pitcher, storage jar, and seed bowl – as well as a headdress and painted buffalo hide robe evidently used in Tesuque Pueblo’s Comanche Dance. These objects joined the museum’s collections at various times between 1901 and 1967.

Stewart Culin (1858-1929), a pioneering and prodigious ethnographer,[7] obtained the headdress – “made from hide, dyed hair, horn, and fabric” – and the painted buffalo robe (“the painted design is of the ‘box-and-border’ type, which is found throughout the central Plains”)[8] from Benham Indian Trading Company in Albuquerque in 1907.

The ceramic pieces came from three sources: Colonel James Stevenson (1840-1888),[9] a geologist of broad interests who served with the Hayden Survey from 1872-1878 and joined John Wesley Powell’s fledgling Bureau of American Ethnology in 1879, obtained the pitcher at Tesuque in 1879.[10] The museum bought the storage jar in 1902 from “Captain” C.W. Riggs,[11] an enterprising dealer in Native American objects, who acquired it at Cochiti sometime between 1876 and 1891. The seed bowl came to the museum via an estate donation in 1967.

The descriptions of the objects referenced by this notice are far more helpful than the pithy, astonishingly uninformative text linked to far too many NAGPRA notices of intent to repatriate. Many of the notices leave readers unable to visualize what sort of object is being discussed. This would appear to negate NAGPRA’s capacity for educating curators, dealers, and collectors with specifics about the objects covered by its broad umbrella. But here, for example, we learn that the storage jar Riggs picked up at Cochiti “is decorated with black designs – corn and circular motifs – on white pigment; the lower portion is painted red….it’s [sic] solid lines (without ceremonial breaks), wide mouth and tapered lower half, lack of human and animal figures, and presence of floral motifs all support a Tesuque origin.”[12]

The museum concurred with claimants’ contention that the five pieces qualified as sacred objects and objects of cultural patrimony under NAGPRA, and should be given to the Pueblo of Tesuque in New Mexico.

Three Coast Salish Masks

Sacred Objects

The Field Museum, Chicago, IL (Sept. 3, 2019): “At an unknown date, three cultural items [masks] identified as Salish in the Field Museum’s records were removed from an unknown location and sold to H. Stadhagen [sic], a purveyor of indigenous material culture.” In 1902, Charles Newcombe (1851-1924),[13] a British physician and ethnographic researcher whose career found him collecting numerous pieces of indigenous Northwest Coast manufacture for various institutions, purchased the masks from “H. Stadhagen’s [sic] Indian Curio store in Victoria, B.C.” on behalf of the museum. Stadthagen’s was one of the early entrepreneurial establishments that helped transform Northwest Coast indigenous art into a business, and also turned Victoria into the effective hub of that enterprise.[14]

The notice states the museum’s intention to return the masks to the Samish Indian Nation in Washington. Unfortunately, the notice does not tell us anything about the masks’ appearance, much less their role in Salish life beyond the formulaic statement that they “are an integral part of rituals and ceremonies performed by Coast Salish traditional religious leaders.”

Five Haundenosaunee/Iroquois (Cayuga) Wooden Masks

Sacred Objects

New York State Museum, Albany, NY (Aug. 5, 2019): The museum received five wooden Haudenosaunee masks as donations from poet, philanthropist, and Indian rights activist Harriet Maxwell Converse (1836-1903). According to the notice, “one of the medicine faces was reportedly made in Canada about 1779.” The museum agreed with the Haudenosaunee Standing Committee on Burial Rules and Regulations:[15] the five masks should be transferred to the Cayuga Nation in New York.

Although the notice mentions five masks, it provides no description of them or their role in Haudenosaunee society, and produces no information about provenance beyond that already noted. As a side note, by my rough count no fewer than seventy-five masks and nine wampum belts that Converse gave to the museum have been repatriated since NAGPRA went into effect.

Winnebago Medicine Bundle

Sacred Object

Nebraska State Historical Society, DBA History Nebraska, Lincoln, NE (Aug. 5, 2019): In 1922, Robert B. Small donated a Winnebago bundle to the museum. Small, who worked as a clerk at the Winnebago Agency, received it more than fifty years earlier – meaning, circa 1870 – as a gift from Joseph Harrison, a Winnebago. According to Harrison, the bundle “had kept away the evil spirit and also given him good luck in war and in peace.” He evidently trusted it would perform a similar function in Small’s life. (As the notice explains, “Harrison gave the bundle to his old friend…believing it would bring him good fortune too.”)

Although the notice describes the bundle as a sacred object which should be turned over to the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska, it provides absolutely no helpful information about the piece, its provenance, contents, function, associations, or role in Winnebago culture.

Blackfeet Beaver Medicine Bundle

Object of Cultural Patrimony

Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Plains Indian Museum, Cody, WY (July 19, 2019): According to the notice, in 1965 artist-collector Paul Dyck (1917-2006) obtained a circa-1860 Blackfeet Beaver Medicine Bundle from Dan Bull Plume, Sr., of Browning, Montana.[16] Pioneering anthropologist, Clark Wissler (1870-1947) described this type of physically large, spiritually potent manifestation of sacral power as “the bundles par excellence.”[17]

The notice informs us that Dyck loaned the bundle to the museum in 2006. In 2007, a year after Dyck’s death, his foundation changed that loan into a gift. The following year, “members of the Blood Tribe (Canada) Spiritual Advisors, consisting of Horn Society advisors and members, viewed the Beaver Medicine Bundle…, confirmed its identity, and affirmed that Beaver Bundle Ceremonies associated with this bundle are still practiced by both the Blackfoot Nation of Canada and the Blackfeet Tribe of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana.”

The museum agreed to repatriate the Beaver Medicine Bundle to the Blackfeet Tribe of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation in Montana.

Please note: This column does not offer legal or financial advice. Anyone requiring such advice should consult a professional in the relevant field. The author welcomes readers’ comments and suggestions, which may be sent to him at legalbriefs@atada.org

NOTES

[1] Lynda V. Mapes, “Lummi Tribal Members Could Sue Under Repatriation Act to Free Captive Orca in Miami,” The Seattle Times (July 27, 2019), https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/environment/lummi-nation-could-sue-under-repatriation-act-to-free-captive-orca-in-miami/; Kie Relyea, “Saying They’re Family, Lummi Nation Gives These Endangered Orcas a New, Ancestral Name,” The Bellingham Herald (Sep. 10, 2019), https://www.bellinghamherald.com/news/local/article234443642.html.

[2] “Any institution or State or local government agency (including any institution of higher learning) that receives Federal funds and has possession of, or control over, Native American cultural items [is a museum, for purposes of NAGPRA]. Such term does not include the Smithsonian Institution or any other Federal agency. [25 USC 3001 (8)].” “NAGPRA Glossary,” National NAGPRA (National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d.), https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nagpra/glossary.htm

[3] Under NAGPRA, “cultural Items” means: “Human remains, associated funerary objects, unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, cultural patrimony.” Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] For Allen see Clarissa W. Atkinson, “In Memoriam: Hope Emily Allen (1883-1969 [sic]),” 14th Century English Mystics Newsletter, 9 (4) (Dec. 1983): 210-217.

[7] Culin’s writings are noted in “Guide to the Culin Archival Collection” (Brooklyn Museum, n.d.), https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/research/culin/; also “Online Books by Stewart Culin” (The Online Books Page, n.d.), http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Culin%2C%20Stewart%2C%201858-1929.

[8] According to the notice: “Representatives from Tesuque said that this robe was used in the Comanche Dance and was likely purchased from Comanche traders for the purpose.”

[9] Stevenson was married to pioneering American female anthropologist Matilda Coxe Stevenson (1850-1915). Like her husband, she formed part of J.W. Powell’s elite crew of ethnographers when the Bureau of American Ethnology opened for business in 1879. Joy Harvey, “Matilda Coxe Stevenson (1850-1915),” in Marilyn Ogilvie and Joy Harvey, The Biographical Dictionary of Women of Science: Pioneering Lives from Ancient Times to the Mid-20th Century (Abingdon, Oxon, Great Britain: Routledge, 2003), 1232-1233. See, also, Darlis A. Miller, Matilda Coxe Stevenson: Pioneering Anthropologist (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007).

[10] Stevenson’s pitcher joined the collections of the U.S. National Museum; it was purchased by the Brooklyn Museum in 1901.

[11] The rank appears to be an honorific term, as Chauncey Wales Riggs’ name does not appear in Francis B. Heitman, Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army from Its Organization, September 29, 189, to March 2, 1903, 2 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1903). Riggs earned a reputation as a digger of burial mounds in the eastern Arkansas, during which his predilection “unscientific excavation” was on display. “Captain CW Riggs (Biographical details),” (The British Museum, n.d.), https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=199902. For a photograph of the colorful Riggs, see Robert C. Manifort, Jr., Sam Dellinger: Raiders of the Lost Arkansas (Fayetteville: The University of Arkansas Press, 2008), 21.

[12] Consultants from Tesuque “identified this jar as one that would have been owned and used by Tesuque’s Warrior Society.”

[13] Kevin Neary, “Newcombe, Charles Frederic,) in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 15 (Toronto: University Tronto/Unversité Laval, 2005), http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/newcombe_charles_frederic_15E.html.

[14] “The early tourist trade emerging in that city [Victoria] in the 1870s displayed a keen appetite for carvings, baskets, and totems, an appetite that grew over time. Between 1880 and 1912, five different curio businesses operated in Victoria. While they serviced the special needs and requests of collectors and curators, these curio dealers also supplied the hungry and less discerning tourist market. Aaronson’s Indian Curio Bazaar on Government Street claimed to be ‘the cheapest place on the Pacific Coast to buy all kinds of Indian Baskets, Pow-Wow Bags, Wood and Stone Totems, Pipes, Carved Horn and Silver Spoons, Rattles, Souvenirs, Novelties, Etc.” Over on Johnson Street, Hart’s Indian Bazaar respectfully invited the public, ‘especially tourists,’ to visit this shop with the ‘largest and finest assortment of curios on the Pacific coast.’ At Stadthagen’s Indian Trader, 79 Johnson Street, collectors could buy not only trinkets and baskets, but also large totem poles.” To this list should be added Frederick Landsberg’s “curio shop,” the largest of the lot. See Margaret Horsfield and Ian Kennedy, Tofino and Clayoquot Sound: A History (Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 2014), n.p. accessed online Oct. 20, 2019. For the emergence of markets for selling, buying, and reselling Northwest Coast indigenous art see Dennis Cole, Captured Heritage: The Scramble for Northwest Coast Artifacts (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995).

[15] For information about the Haudenosaunee Standing Committee on Burial Rules and Regulations see “Haudenosaunee Repatriation Committee” (Haudenosaunee Confederacy, 2018), https://www.haudenosauneeconfederacy.com/departments/haudenosaunee-repatriation-committee/.

[16] A note of purposes of disclosure: I served on the board of Dyck’s research foundation after the purchase date referenced here and prior to its transaction with the museum. Dan Bull Plume’s deep involvement in Blackfeet spiritual life is attested to in Adolf Hungry Wolf, The Blackfoot Papers [Vol. 2]: Pikuni Ceremonial Life (Skookumchuck, BC, Can.: The Good Medicine Cultural Foundation, 2006), 454-455; Donald Duane Pepion, “Blackfoot Ceremony: A Qualitative Study of Learning,” Ed.D. thesis, Montana State University-Bozeman (Dec. 1999),111. For a photograph of an image of Dan Bull Plume by artist Winold Reiss (1886-1953), see “Dan Bull Plume,” Winold Reiss: Life, Works, Studio Circle” (The Reiss Partnership, 2014), https://www.winoldreiss.org/works/artwork/portraits/A474.htm.

[17] Clark Wissler, “Ceremonial Bundles of the Blackfoot Indians,” Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, 8, pt. 2 (1912), 169.